Ivan Savvich Nikitin facts from the biography. Ivan Savvich Nikitin - interesting data and facts from life

Nikitin, Ivan Savvich

Poet, born September 21, 1824 in Voronezh; mind. On October 16, 1861, his great-grandfather, Nikita Gerasimov, and grandfather, Evtikhy Nikitin, were deacons of the Nativity Church in the village of Kazachya, Zasosensky camp, Zadonsk district, Voronezh province. Nikitin's father Savva Evtikhievich was assigned to the Voronezh philistines and was engaged in trade. Possessing commercial enterprise, he amassed considerable capital, set his trading affairs on a fairly wide scale, had own house, a candle factory and a shop. In addition, he sold candles at the Don and Ukrainian fairs. In all that we know about the poet's father, there is no evidence that he was a man who stood above the environment and with a certain share of mental interests, as the biographer of the poet De Poulay, who knew him, characterizes, but there is no doubt that Savva Evtikhievich was not a stupid person. The difficult life school that he went through developed in him a harsh character, autocracy, and despotism. The poet's mother, Praskovya Ivanovna, was a meek, spiritually downtrodden woman who unrequitedly endured the harsh temper of her husband, who also loved to drink. Caring for the son's spiritual food, the upbringing of his spiritual powers were completely absent on the part of the parents, and the child grew up alone. The family situation did not provide material for the development of the spiritual forces of the child, entailed premature seriousness, concentration, and alienation. The future poet drew his main spiritual food from nature and from acquaintance with the fantastic world, the source of acquaintance with which, according to some sources, was a nanny, according to others, an old watchman at his father's candle factory. The boy began to be taught when he was six years old; the first teacher was a shoemaker. Apparently, however, besides him, Nikitin had another teacher, since in 1833 he immediately entered the second class of the parish theological school. In 1835, he moved to the first, lower, department of the Uyezd Theological School, and in 1837, to the higher department. Nikitin studied at the religious school very well, but the harsh way of life, the heavy atmosphere of the school did not give any healthy food for the mind and heart of the boy, and still he drew it from communication with nature. This was now joined by reading, to which he indulged himself "with all the ardor and enthusiasm." It was of a random nature, it was unsystematic, but, nevertheless, it provided at least some material for reflection, distracted from the difficult impressions of the school and family situation. Alienation, concentration, which were found in Nikitin in early childhood, began to develop even more. In the autumn of 1839 the poet moved to the Voronezh Theological Seminary. Historical data on its state during the era of Nikitin's stay in it speak for the fact that if certain teachers could have some effect on the mental development of the future poet, then in general they could not have a significant impact on his spiritual growth, on broadening his horizons, on excitation of broad mental inquiries and interests. At least, N. did not keep good memories of the seminary, did not have warm feelings for her; he described it in his "Diary of a seminarian" in the most dark colors. Nikitin owed his spiritual growth mainly to reading, to which he devoted himself with enthusiasm. Reading, acquaintance with Belinsky had a tremendous impact on the expansion of Nikitin's mental outlook, on the deepening of his worldview, on the excitement literary interests and gave impetus to the first poetic experiments. He showed the first poem he wrote to the teacher of Russian literature Chekhov, who praised him and advised him to continue.

Nikitin thought of moving from the seminary to the university. At this time, his father's trading business was greatly shaken and by 1843 fell into decay. Along with this, the father began to drink more and more, his harsh character began to manifest itself even more strongly. Under the influence of his father's despotism, his drunkenness, the poet's mother also began to drink. A heavy, suffocating atmosphere was created in the house, which had a detrimental effect on H-on's classes. It seemed that the prospect of entering the university should have served as a strong incentive to overcome seminary scholasticism as soon as possible, but N. studied worse every year, skimped on lessons and, finally, completely abandoned classes. Apparently, in addition to family conditions, the fact that the introduction of a new rule in 1841 made the seminary regime even more difficult played a role in this. Having abandoned the seminary, Nikitin devoted himself entirely to reading and devoted himself to creativity. Having shown one poem to Chekhov, the poet carefully hid his further poetic experiments from those around him. In 1843, Mr.. N. was dismissed from the senior class of the middle department of the seminary "for lack of success, because of not attending the class." To fully graduate from the seminary, it was necessary to stay two more years in the last, senior, department. Having fallen in love with literature, filled with high aspirations and poetic dreams, the aspiring poet immediately after leaving the seminary had to plunge into the most difficult worldly prose and sit down at the counter in his father's candle shop, helping him sell candles on the market square. Six months later, the poet's mother died. Her death had a strong effect on her father, he began to drink even more and completely abandoned trading. The house, candle factory and shop were sold. With the proceeds, Savva Evtikhievich bought a bad inn and rented it out. The income from the yard was so insignificant that it was not enough to meet the most basic needs. Nikitin made an attempt to offer his services as a clerk or clerk, but the Voronezh merchants, seeing their father's drunkenness, were also distrustful of their son. But she had enough inner stamina to completely lose heart. He refused the tenant and began to run the inn, performing all the functions of a janitor, up to running for vodka for cabbies. From then on, things went better for N. and soon it became possible to build a small wooden outbuilding in five rooms, of which three were rented to the seminary teacher I. I. Smirnitsky.

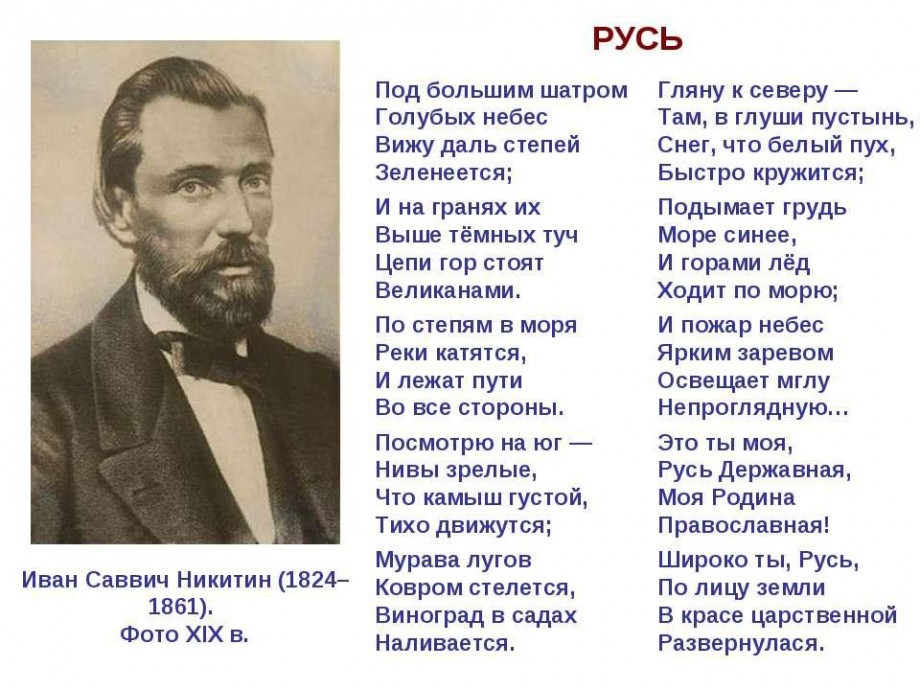

Despite the difficult family situation, N. did not sink morally: the mental demands inherent in the seminary did not die in him, his interest in reading did not disappear, and his literary inclinations did not die out. Selling candles, then keeping an inn, struggling with poverty, N. continues to be interested in literature, seeks to understand his experiences, to develop a certain worldview. With his development and impressionability, he deeply felt the discrepancy between the surrounding reality and dreams and aspirations, and a feeling of dissatisfaction with life was the main feature of Nikitin's psyche at that time. The concentration that arose in childhood under the influence of the difficult environment of 1843-1853. developed even more; Surrounded by an environment that could not understand him, N. became even more withdrawn into himself. The only person with whom Nikitin shared his inner feelings, impressions, poetic ideas was I. I. Durakov, a young tradesman who supported the poet morally, strengthened his faith in poetic forces. Under the influence of Durakov, Nikitin in October 1849 decided to send two of his poems - "Forest" and "Duma" to "Voronezh. Gub. Ved.", Without giving his last name. V. A. Sredin, N. I. Vtorov and K. O. Aleksandrov-Dolnik, who were then at the head of the newspaper, became very interested in the author. November 5 at No. 45 "Voronezh. Gub. Ved." (Separate second, part of the unofficial, p. 314) was printed: “The other day, two poems were sent to us from an unknown person in a letter signed with the letters I.N., which we, after reading, found so wonderful that we would be ready for this time, out of respect for talent, deviate from the program we have adopted and place them in our newspaper. The only obstacle that keeps us is our ignorance of the name of the author. " Despite this flattering note for Nikitin, he did not respond to it. Only four years later, on November 6, 1853, Nikitin again sent his poems to the editor of the "Pantheon" F. A. Koni with a letter that he signed with his full name. Almost simultaneously, on November 12, 1853, the poet sends three of his poems - "Field", "Rus" and "Since our immense world ..." to the editorial office of "Voronezh Gub. Vedas", this time already without hiding his name and saying that he is a Voronezh tradesman. The editors of the newspaper reacted with great attention to Nikitin's new letter. Vtorov was especially interested in him; he sought out the poet, the first to take a decisive step towards rapprochement with him. November 21, 1853 in No. 47 "Voronezh Province. Ved. "(part of the unofficial, mixture, pp. 283-284) one of the poems sent to N. - "Rus" was printed. In its patriotic spirit and tone, "Rus" just fell into the mood of Russian society at the beginning of the Crimean campaign. In this Vtorov, who was then an adviser to the Voronezh provincial government, and Alexandrov-Dolnik, who held the position of deputy chairman of the Civil Chamber, were very sympathetic to N., introduced him to the local circle that was grouped around them intellectuals. Its members were very diverse in age, social and official status, profession and educational qualifications. The interests of the members of the circle were extremely diverse. Many members were united by a common interest in studying the local region, in social life and in literature. From speeches in the press, with acquaintance with the Vtorovsky circle begins new period N.'s life, he falls into another sphere, under the influence of new influences. Nikitin, according to Vtorov, at first was slow to approach him. Only when he got to know Vtorov closer did the poet get along with him and with the members of his circle, despite the fact that he was greeted by them as a dear, welcome guest. Here, alienation, isolation, developed by difficult living conditions, affected. According to Vtorov and De Poulet, Nikitin immediately after his appearance in the press became very popular in Voronezh. Success, a mass of new impressions, the warm friendly participation of Vtorov and his circle had an encouraging effect on the poet, on the excitement of his creative forces. Nikitin's alienation began to pass, his circle of acquaintances began to expand. The historian became very interested in the poet, later chairman of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities, gr. D. N. Tolstoy, then vice-director of the police department, a good friend of Vtorov, who told him about Nikitin and sent him several of his poems. Gr. Tolstoy published in the second April book of The Moskvityanin for 1854 Vtorov's letter to him about Nikitin with his poems sent and invited the poet to publish a collection of poems. Soon appeared in the June book "Father. Zap." for the same year, an article about N. by one of the members of the Vtorovsky circle, A.P. Nordshtein, along with which 9 poems of the poet were published. N. V. Kukolnik, who met the poet in Voronezh, welcomed Nikitin in the July book "The Bible for Reading" in "Leaves from a Russian Notebook". After that, he began to place his poems in "Father. Zap." and "Bible. for reading." By agreeing to the proposal Tolstoy, Nikitin devoted himself entirely to preparing a collection of his poems. Creative work went on with surprising intensity: N. writes a number of poems, reworks several times already written. At the same time, he is working on a large work - "The Fist". N.'s popularity in Voronezh was growing, sympathy for him was expressed by the most diverse social strata, alienation and unsociableness disappeared, he was in a cheerful and cheerful mood. But this cheerful mood was overshadowed by a disorder of physical health - a disease of the stomach; the attacks of the disease were particularly severe in December 1854 and April 1855; in the autumn his health began to improve and he energetically set to work; October and November were very productive. Having written a number of works, while continuing to work on "The Fist", the poet at that time conceived another great work, later called "Taras". In February 1856, a collection of Nikitin's poems was published, which included 61 poems. On the advice of Mr. Tolstoy, N. presented the collection to members of the Imperial family, from whom he received a number of gifts. In the costs of publishing the collection, which amounted to 300 rubles, he took part, except for gr. Tolstoy, his acquaintance A. A. Polovtsev. Having met success from the very first steps in the literary field and becoming a short time popular, N. experienced failure, a cold and even sharply negative attitude towards criticism, as soon as he came out with collections of his poems. Chernyshevsky, who was then at the peak of critical fame, spoke most negatively about the collection in Sovremennik (1856, book IV). Negative Feedback critics made a strong impression on the poet, but, as can be seen from his letter to Kraevsky dated August 20, 1856, N. realized that he had come forward with the collection prematurely, when his poetic powers had not yet strengthened. N. did not lose heart, feeling that now they have developed, and energetically continued to work. Having begun, as already noted, in 1854 the great work The Fist, the poet did not stop working on it all the time; in September 1856, the work was completed, but countless alterations and amendments followed, significantly changing the Fist.

In 1856, the poet became interested in the governess of the landowners Plotnikovs, M. I. Junot. As far as the surviving data allow us to judge, she was a lively, poetic nature, sensitive and developed. The poet, apparently, had a serious feeling for her and enjoyed her reciprocity, but both were fraught with feelings, did not fully express themselves.

Once in the sphere of new life relationships, speaking in the literary field, making extensive acquaintances, N. did not change his life situation, continuing after 1853 to maintain an inn with his father; the latter began to generate income and N. came out of need. The poet's father continued to drink, but, apparently, family relationships in 1854-1856 improved somewhat, and the atmosphere of the inn was no longer so depressing to the poet.

June 25, 1857 Vtorov left Voronezh. The Vtorovsky circle, which began to disintegrate even before his departure, completely disintegrated. His beneficial role in Nikitin's life is undoubted: he not only morally supported the poet, had an encouraging effect on his spiritual mood, but also helped him to enter the wide literary road. The role of the Vtorovsky circle, most of whose members were well educated, in spiritual development N. was that he gave good ground for the spiritual growth of the poet, contributed to his mental development, broadening his horizons, replenishing his education: N. began to work on self-education in the most serious way, fill in the gaps in reading and began to study the French language, in which he helped Vtorov. The departure of the latter from Voronezh is not only an external date in H.'s biography, but also a milestone in his internal development, marking a serious mental crisis that coincided with this departure. After the departure of Vtorov, N. with great acuteness again felt the severity of the life and family situation, a pessimistic mood seized the poet with great force, creative excitement was replaced by a sharp decline in creative forces, complete disappointment in them, and doubt in his poetic talent. In such a difficult state of mind, H. makes latest amendments in the "Fist"; On August 2, 1857, he was sent to Moscow to Alexandrov-Dolnik, who took over the supervision of the printing of the book and its proofreading. At the end of February 1858 "Fist" was printed. By the summer of this year, Nikitin's health was again upset. It got a little better only in the fall. At this time, the rich merchant V. A. Kokorev, whom N. met through Vtorov, took a warm part in the poet. Under his influence, Kokorev took an active part in the distribution of "Kulak". Criticism met him very sympathetically, The Fist had the same success with the public: less than a year after its release, by the end of 1858, it had already sold out.

In October 1858, Nikitin decided to change the life situation that weighed on him - to buy a stone house in Voronezh with the money received from the sale of the book and live on the income from it. This thought was soon abandoned by the poet and a new one appeared to him - to leave the maintenance of the inn, take advantage of the offer made through Vtorov by the society for the cheap publication of books, become his agent and open a book trade. To start the business, he lacked 3,000 rubles, which Kokorev willingly agreed to give to the poet, who offered to publish a collection of poems to cover the debt. The act of Kokorev, "disinterestedly noble," as the poet calls him, aroused deep gratitude in his soul. He immediately ardently, energetically set about organizing the store, filed a petition for dismissal from the bourgeois class, etc. An acquaintance of the poet, N. P. Kurbatov, expressed a desire to be a companion of N. and in the twentieth of December 1858 left for Moscow Petersburg to buy books.

Despite the depressed mood and morbid condition, N. in 1857-1858. still continued to seriously work on his self-education, closely follow Russian literature, fill in the gaps in his knowledge. This is evidenced by the letters of H. 1857-1858. to Vtorov, from which it is clear that he read Cooper, Shakespeare, Hugo, Goethe, Chenier, began to study German, translating Schiller and Heine. This time coincided with the public enthusiasm that marked the first years of the reign of Emperor Alexander II. That interest in public life, in the people, and a negative attitude towards serfdom, which quite definitely manifested itself in N. in 1854-1856, even more, under the influence of the general mood, intensified in 1857-1858.

The work of setting up the store broke N.'s strength; at the beginning of 1859, he fell dangerously ill and fell into a depressed state of mind. On February 22, 1859, the shop was opened. The opening of a bookstore by a popular poet in Voronezh was a whole event in local life. N. and some organs of the metropolitan press showed interest in this enterprise, giving space on their pages to articles about the opening of the store. Seeing in the store the way to get rid of the oppression of his father, from the depressing atmosphere of the inn, H. passionately gave himself up to the book trade, not proportioning his physical strength spending the whole day in the store. Overwork greatly tired the poet, sadly responded to his shaky health, which, in turn, led to a decrease in literary productivity. The poet energetically set to work again in the summer of 1859, preparing a collection of poems. He was very strict about the poems included in the collection published in 1856, excluding more than half from it. Of the poems of the 1856 edition, transferred by the poet to the new edition, many have undergone significant, significant alteration. He treated the poems written after the delivery of the manuscript of the 1856 edition with the same strictness: Nikitin was not satisfied with many of them and did not include them in the new edition. N.'s health began to improve; but in October 1859 it again deteriorated sharply.

In December, a new collection of poems came out of the printing house; It contains 60 poems. Criticism of the collection was met much colder than the appearance of the "Fist".

From the beginning of 1860, Nikitin's health began to improve, his mood became more cheerful, after the decline of his creative forces, an upsurge came, literary productivity rose again; interest in public life, which had fallen in 1859, rose again. Having recovered, Nikitin decided to go to Moscow and St. Petersburg, meaning to enter into relations with publishers and booksellers. In June 1860 the poet left Voronezh. He didn't stay away for long. At this time, N.'s business was going well, in the fall of 1860 it was possible to hire more spacious and better premises for the store. In the second half of the year H. felt good, worked hard and returned to the great work begun in 1855 - "Taras". At the end of 1860, Nikitin wrote "The diary of a seminarian".

By 1859, the poet’s new passion dates back to the daughter of the merchant Mikhailova, whose father was very disposed towards N. According to the testimony of his friend and biographer De Poulet, this feeling was strong, met with reciprocity, but N. suppressed it in himself, realizing that when with his sickness he cannot bring happiness to a loved one. The same fate befell the poet's new hobby, in the middle of 1860, - the daughter of a retired general N. A. Matveeva, who also met with reciprocity.

Nikitin's health, which had deteriorated by the end of 1860, improved again by the beginning of 1861, and his strength again began to rise. He takes an active part in the meetings of the circle grouped around De Poulet, is very interested in local life and public issues. N. manifesto on the liberation of the peasants was greeted with great enthusiasm. From the letters of the poet of this time, it is clear how much he was captured by this event. He greatly sympathized with N. planting public education in the region and took an active part in organizing a literacy society in Voronezh, in establishing Sunday schools, a women's gymnasium, etc. N. looked at his bookstore and library for reading as a cultural enterprise. He did not limit himself to the role of a simple seller, but, when the mental level of the reader and buyer required it, he came to his aid in choosing books, gave advice, and helped to understand the book material. Especially beneficial, according to the opinion of those who knew the poet as a bookseller, was his influence on young people, to whom he gave healthy spiritual food, guided her reading. By 1861, the business of the H. store was already firmly established, and at the same time the store became one of the cultural centers Voronezh.

Throughout the first half of 1861, H. felt physically well, but on May 1 he caught a bad cold. This cold, exacerbating the tuberculous process, turned out to be fatal. In the summer, N.'s health, nevertheless, allowed him to sometimes get out of bed, take a short walk, drive to the store, the care of which did not leave the poet. In the fall, his health began to deteriorate, and N. realized that his days were numbered. On September 10, a spiritual testament was made. The poet appointed De Poulet as executor, and transferred the right to publish his works to Vtorov so that the proceeds would be used for charity. The money received from the sale of the store, Nikitin bequeathed to his family, excluding his father. This was hardly caused by hatred for his father, or rather, it was dictated by the consciousness that he would drink away the money he got, that it would not do him any good. My father had a house, which, according to De Poulet, gave 300-400 rubles. income. For all the time of his illness, the poet experienced the most severe physical suffering, great nervousness was revealed in him, "something like hysterical seizures, constant coughing and diarrhea greatly tormented and exhausted the patient. To these physical sufferings were added moral ones, the source of which was the father. Surrounding the sick De Poulet, Zinoviev and Pereleshin unanimously testify that Father N., despite the serious illness of his son, continued to lead his former way of life, still drank and raged, causing great suffering to the poet. On October 16, 1861, death ended Nikitin's torment. His death was greeted in Voronezh with deep regret.. The Russian press also reacted. N. was buried on October 18 at the Novo-Mitrofanovskoye cemetery, near the grave of Koltsov.

The earliest surviving works of Nikitin date back to 1849. Isolation, concentration in oneself left a certain imprint on the work of H. 1849-1853. The scope of his poetic attention was limited; he mainly revolved in the area of his inner experiences, the surrounding life attracted little attention. During this period of time, the poet's spiritual mood, his desire to comprehend life, his religious mood, and love for nature, to which a significant part of his poems are devoted, clearly affected his work. A red thread is a feeling of dissatisfaction with life, suffering from its inconsistency with dreams and aspirations. However, even at this time, the beginnings of the poet's interest in the life around him, social motives, are already visible, the future poet-citizen is already visible. In 1849-1853 N. was entirely under literary influences. The influence of Koltsov, as well as Pushkin and Lermontov, was especially strong. But at the same time, independence and immediacy are already appearing, mainly in those poems in which N. describes personal experiences and nature. Having been brought up as a poet in Pushkin, Lermontov and Koltsov, N. by 1853 was already quite fluent in verse and artistic speech. Reading - this is the main spiritual food of Nikitin, had a tremendous influence on the development of N.'s worldview and was very noticeably reflected in his works. In the thoughts expressed by the poet in the poems of 1849-1853, there is little independent, and where he tries to give his own resolution to the philosophical questions that tormented him, there is a lot of artificiality, rhetoric borrowed from books of thoughts.

Personal experiences play a prominent role in N.'s work even after he met Vtorov and his circle in November 1853, but along with this, interest in the life around him, in the people, their way of life and psychology, is growing with surprising speed; from 1854, works with a tinge of precisely this kind of interests became predominant, and by 1857 Nikitin became a well-defined social poet. Conceived in this era, two large works - "Fist" and "Taras" are entirely devoted to the depiction of petty-bourgeois and folk life. N. increasingly strives to be more direct, avoids rhetoric, "philosophizing", which previously occupied a prominent place in his poetry. In the work of 1854-1856. just as before, the influence of other poets is visible, but to a much lesser extent than before; the desire to become independent, to go his own way, is more and more revealed. All this was a consequence of the natural growth of N.'s poetic powers, flowed from the development of his artistic consciousness, but the influence of members of the Vtorovskaya circle undoubtedly played a certain role. In the work of 1857-1858. subjective experiences, personal suffering, melancholy, depressed state of mind are already harmoniously combined with social motives. In them there is nothing artificial, grossly tendentious, a desire to imitate the prevailing mood of society: they are deeply sincere manifestations of H.'s inner world, a product of sincere sympathy for the people's suffering. In 1859 - 1861. N. continued to follow the road he had taken earlier, fully joining the contemporary realistic school. But the social element did not suppress the artistic; the poet managed in a purely social work - "Diary of a seminarian" to remain true to artistic truth. In 1860-1861. N. won wide public sympathy, taking first place among public poets after Nekrasov, who greatly appreciated Nikitin. Along with the recognition of Nekrasov, a representative of a completely different literary movement, the aesthetic critic Apollon Grigoriev, was sympathetic to Nikitin's poetry. By 1860, the gradually developing poetic forces of N. began to flourish, but death interrupted this flowering, they did not have time to show up completely. In terms of his artistic talent, N. was not a major poetic figure, but his poetry stands high in terms of its permeating humanism, deep sincerity, feeling, and height of spiritual disposition. This side of N-a's poetry attracted public sympathy for him, including L. Tolstoy, and created for him wide popularity, which he has not lost to this day: his works have withstood a huge number of editions.

1. Editions of Nikitin's works. Poems, ed. gr. D. N. Tolstoy. Voronezh, 1856; poems, ed. B. A. Kokoreva, St. Petersburg, 1859; essays, ed. A. P. Mikhailova. Voronezh, 1869; 2nd-13th ed. K. K. Shamov and t-va I. D. Sytin. M., 1878 - M., 1910; anniversary edition t-va I. D. Sytin, M., 1911; ed. "Modern. to-va" M., 1911; ed. A. S. Panafidina, ed. M.O. Gershenzon (two ed.) M., 1912; ed. t-va "Activist", ed. S. M. Gorodetsky, St. Petersburg, 1912. In addition, many school publications were published. The Complete Works have been published since 1913, ed. A. G. Fomina, in ed. "Enlightenment" in St. Petersburg.

II. Letters from Nikitin. To L.P. Blummer, - "Light", 1861, book. XII; N.I. Vtorov and M.F. De-Poulet in the composition. them biographies, pridozhen. to 1-13th ed. writings by Nikitin; to gr. D. N. Tolstoy, - Commemorative book Voronezh. lips. for 1894 Voronezh, 1894 and "Vsemirn. Vestn.", 1904, book. IX; to I. I. Bryukhanov, - "Philological Zap.", 1901, c. IV-V (Materials for the biography of Nikitin), separately - Voronezh, 1902 and "Proceedings of the Voronezh. Archiving. Commission", 1904, no. II; to the Plotnikovs, - "Shchukinsky Collection", 1905, no. IV; to P. M. Vitsinsky, - "Peaceful Labor", 1905, book. I; to F. A. Koni, - "Russian Arch.", 1909, book. XI and A. F. Koni "Memoirs"; to V. A. Kokorev, - Barsukov. Life and works of Pogodin, book. XIII; to A. A. Kraevsky, - "Vestn. Evr.", 1911, book. x; to N. I. Vtorov in the article by S. Kavelina "New data on the characterization of Nikitin", - "Russian. Ved.", 1911, 16 Oct. and separately; to K. O. Aleksandrov-Dolnik, - "The Way", 1911, November.

III. Bibliography. A. M. Putintsev, Materials for a bibliography about Nikitin and his writings, - "Scientific Notes of the Yuryevsky University", 1906, II and separately.

IV. Memories. De Poulet, - "Voronezh. Gub. Ved.", 1863, No. 12; A. L. (Shklyarevsky) in the book "Russian Criminal Chronicle", St. Petersburg, 1882; De Poulet and Vtorov in the biography of Nikitin, comp. De Poulet and App. to 1-13th ed. essays; S. I. Miropolsky in school. ed. the work of Nikitin, edited by S. I. Miropolsky (M. 1885 and in the last ed.); P. V. Tsezarevsky, - "Baltic. Sheet", 1899 and, Son of the Father. "1899, No. 286; S. Karpov, - "Don", 1899, No. 107; F. Berg, - "Russian. Leaf." 1899, No. 14 and "Voronezh. Tel." 1899, No. 15; E. I. Sabinina in A. Vdovenkova's book "Protoier. E. I. Sabinin" and "Voronezh. Tel." 1910, No. 70; "Memories of Nikitin by his contemporaries." - "Voronezh. Telegr.", 1911, No. 233 (reprinted memoirs of Miropolsky, Pezarevsky, Karpov, Sabinin, Berg); "Memories of Nikitin by his relatives", - "Voronezh. Tel.", 1911, No. 234, "Don", 1911, Oct. 21 and "St. Petersburg. Ved.", 1911, October 16; S. P. Pavlova, - "Don", 1911, October 16; T. Donetsk, - "The Living Word", 1911, No. 229; "Village Teacher" in the article by S. H. Pryadkina, - "Voronezh. Tel.", 1911, No. 234, app.

V. Biographical materials. Biography of DePoulet, appended. to 1-13th ed. sochin. Nikitin; A. M. Putintsev. Sketches about the life and work of Nikitin - "Memorial book of the Voronezh province for 1912" and separately: Voronezh, 1912; V. I. POKROVSKY. I. S. Nikitin, his life and works. Digest of articles. M., 1910; biographical essay by M. O. Gershenzon, edited. them publishing essays. Nikitin; F. E. Sivitsky. Nikitin. SPb., 1893; A. P. Nordshtein. News of literature, sciences and industry. - "Father. Zap." 1854, ХСІV, book. VI; A. I. Nikolaev. Lists of windows course to Voronezh. spiritual seminary, with an extract from the seminary. archive of information about persons who taught. in the seminary. - "Voronezh. Diocese. Vedom.", 1882, No. 19 and separately; Voronezh. anniversary collection in memory of the 300th anniversary of Voronezh, vol. II. Voronezh, 1886; N. Polikarpov. Nikitin as a pupil of Voronezh. spiritual seminary. - "Voronezh. Telegraph", 1896, No. 119; N . Yevtey Nikitin is the poet's grandfather. - "Voronezh Telegraph", 1911, Nos. 237, 241, 243 and 248; To the biography of Nikitin. - "The Living Word", 1911, November 9, 13, 15, 26; New data from the biography of Nikitin. - "Living Word", 1911, 6 Oct.; A. G. Fomin. Illness and last minutes life of Nikitin. According to unreleased. mater. - "Contemporary", 1912, book. v.

VI. Criticism. A. V. Druzhinin. Works, vol. VII. SPb., 1865; N. G. Chernyshevsky. Works, vol. II. St. Petersburg, 1906; N. A. Dobrolyubov. Works, ed. M. K. Lemke, vol. II and IV. SPb., 1912; J. K. Grot. Proceedings, vol. III, St. Petersburg, 1901: N. E. Mikhailovsky. Works, vol. IV. SPb., 1897; I. Ivanov. New cultural force. SPb., 1901; H. A. Savvin. Nikitin. Nizhny Novgorod. 1911; All in. E. Cheshikhin. Russian history. lit. 19th century III, part III, ed. t-va Sytin; A. M. Skabichevsky. The history of the latest Russian lit. 7th ed. St. Petersburg, 1909; "Russian Vestn.", 1856, vol. II, April, book. I, modern letop., pp. 191-196; De Poulet, "Russian Word", 1860, book. IV, sec. II, criticism, pp. 1-22; A. Suvorin, "Vestn. Evr.", 1869, v. IV, book. VIII. pp. 891-903; "Case", 1869, book. VII, hob. books, pp. 47-56; "Otech. Zap.", 1869, v. 185, book. VIII, sec. II, pp. 292-305.

A. G. Fomin.

(Polovtsov)

Nikitin, Ivan Savvich

Talented poet; genus. in Voronezh on October 21, 1824, in a petty-bourgeois family. He studied at the Theological School and the Seminary. The father, at first a rather wealthy merchant, hoped to send his son to the university, but his affairs were upset, and N. was forced to become an inmate in the trade in wax candles. N.'s adolescence and first youth present an extremely sad picture of need, loneliness, incessant insults to pride, depicted by him later in the poem "The Fist". The bullying of a drunken fist over his daughter, over his wife, reproaches with worries about their food - all these are personal memories of the poet himself. Among his comrades, N. also remained unsociable and lonely. His only consolation is communion with nature; in the poem "The Forester and the Grandson" he himself tells a fascinating story of the awakening of poetic talent under the influence of the simplest, but hotly perceived natural phenomena. Only by chance N. learned about Shakespeare, Pushkin, Gogol and Belinsky and read them furtively, with the greatest zeal. In the "Diary of a seminarian" N. tells in detail how difficult it was for him to get acquainted with the most, apparently, accessible works of literature. He could later proudly say that he owed all his development "only to his own energy." She does not lose heart and during trading activities N. He changes the candle shop for an inn, plunges into the "suffocating air" of cabbies, petty settlements, civil strife with workers; but his favorite writers still haunt his desk. Koltsov's songs made a particularly strong impression on the gifted tradesman and "janitor": N. decided to apply with his poetic experiments to the editors of the Voronezh Gubernia. The patriotic poem "Rus", written about the Sevastopol war, finds a favorable reception, and from that time N.'s popularity began, first in Voronezh . The following year, the poet begins his main work - the poem "The Fist" - and prepares the first edition of the poems, which was published at the beginning of 1856 and was a great success. In 1857, The Fist came out and, by the way, evoked a very favorable response from Academician Grot. At the same time, N., thanks to the consent of V. Kokorev, to give him a loan against the complete collection of his works, he opened a bookstore, which became the center of the Voronezh intelligentsia. The second edition of his poems, at the request of the publishers, appeared without the "Fist". Despite his literary success, N. did not get along with literary circles; it was as if he felt to the end the dazedness with which he wrote his first letter to the editors of Voron. Lips. Ved. Neither in Moscow nor in St. Petersburg, where N. went on book business, did he get acquainted with writers, finding their society and himself uninteresting to each other; traces of seminary alienation and years of struggle with want remained indelible. The last great work of Nikitin is "Diary of a seminarian"; it is a mournful autobiography that further exacerbates the old wounds of youthful deprivation and resentment. At the same time, the poet tried to finish his long-begun poem "The City Head", but a rapidly developing illness interfered with his work. N. enthusiastically greeted the manifesto on February 19: it was the last vivid manifestation of the poet's moral life. It gradually faded away, as can be seen from Nikitin's correspondence with a girl he knew who lived near Voronezh. Letters - friendly content and are in the nature of a sincere confession. In general, there are no romantic motives in N.'s life: while he was hosting an inn, there was nothing to think of finding an intelligent hostess, and then an incurable illness developed, and N. could not allow the thought of linking someone else's fate with his infirmities. Most often, the poet, as if anticipating the near end, reminisces in his letters: “I shudder when I look back at the joyless, long, long path I have traveled. How much strength I put on it! And for what? I won for many years by killing my best time , your golden youth? After all, I haven’t put together, I couldn’t put down a single carefree, cheerful song in my whole life! ”The famous elegy:“ A deep hole was dug with a spade ”is the same testament in verse: it ends with itself“ Diary of a seminarian. ”D. N. Oct. 16 1861. The first posthumous edition of his works was published in Voronezh in 1869, the next - in Moscow, in 1878 and 1883. All these editions are incomplete, cut down by censorship or publishers. The first complete edition was published in 1885, under the editorship of de Poulet, one of the poet's close friends, with a detailed biography and excerpts from N.'s letters. Nekrasov on N. was short and shallow. The similarity of motives was prompted partly by the similarity of living conditions, partly by the similarity of talents. The original and essential feature of N.'s poetry is truthfulness and simplicity, reaching the most rigorous direct reproduction of everyday prose. All of N.'s poems fall into two large sections: some are devoted to nature, others to human need. In both those and others, the poet is completely free from any kind of effects and idle eloquence. In one of his letters, N. calls nature his "moral support", "the bright side of life": she replaced him with living people. He does not have vivid pictures, lengthy descriptions; for him, nature is not an object of purely aesthetic pleasures, but a necessary and only source of moral peace and consolation. Hence, N. uncomplicated and uncomplicated pictures of nature. In public poetry, he almost does not leave the circle of real and popular life and depicts it without the slightest encroachment on the sensitivity and temptation of colors. "The charm is in simplicity and truth," N. wrote to his correspondent. Throughout his life he resented big buzzwords like "disappointment"; and involuntarily suspected the sincerity of a poet or publicist, since their speech was distinguished by a special outward beauty. N. touched on almost all the dramas that take place daily in folk life: family strife between parents and children, divisions between brothers, fathers' despotism over daughters, mother-in-law's hatred for daughter-in-law, wives - for their despot husband and barbarian, the fate of foundlings. And nowhere does the poet change his restrained, as it were, impassive mood. Only a few lines are devoted to the sale of a daughter by poor parents, but the poet is able, with a fleeting remark, to illuminate the terrible abyss of moral stupidity under the influence of hopeless need. The poem: "The Old Servant" is a simple, historically accurate account of recent slavery and its corrupting influences. N.'s best work, "The Fist", is both an autobiography of a man and a lyrical confession of a poet. The introduction to the poem is the best characteristic of N.'s talent and creativity:

Not for fun, not out of boredom

How could I compose my verse

I embodied the pain of the heart into sounds

My soul was close

All the dirt and poverty of the kulak!

The main idea of the poem is the story of the human soul, ruined by poverty and inseparable humiliations. It is in the full sense suffered by the poet himself. Hence, with the photographic simplicity of the paintings - their deep drama, with completely prosaic heroes - the deep social meaning of their history. N. shows how the "fatal force of need and petty evil" does not kill instantly, but strangles its victims gradually until they suffocate in mud and hunger. The poet himself escaped this fate, but salvation was bought at a high price: an instinctive distrust of human truth and sincerity, the loss of his best years in the struggle for a piece of bread and personal independence. N. is one of the countless Russian talented people in external position, but one of the rare ones who managed to win back both talent and freedom, and die with a proud and legitimate consciousness of victory.

Iv. Ivanov.

Biography of N., compiled by de Poole, originally appeared in the "Russian Archive", 1863; in the same journal in 1865 for the first time printed. several poems by N. ("Headman", "Prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane", "To the accuser poet") and the story "Liberal" (the last - in 1867). N.'s poem "Philanthropist" for the first time printed. in "Russian Antiquity" 1887, vol. LIII. There is a school edition. op. N., ed. S. Miropolsky (2nd ed. M., 1889). Separate ed. poem N. "Fist". N.'s poems are subtly conveyed on it. lang. G. F. Fiedler ("Gedichte von Iwan Nikitin"; Lpts., 1896, ed. Advertising). For the biographical library of Pavlenkov, the biography of N. was written by E. Savitsky (St. Petersburg, 1893). Detailed characteristics N. in the article: "The Poet of Bitter Truth" ("Rus. Thought" 1896, Jan.).

(Brockhaus)

Nikitin, Ivan Savvich

Poet and novelist. Genus. in Voronezh in the family of a wealthy tradesman, the owner of a candle factory. After graduating from a religious school in 1839, he moved to the Voronezh Theological Seminary, from where he was expelled "due to little success." Nikitin hoped to get into the university, but difficult material and family conditions forced him to become the owner of an inn. Nikitin began to write while still in the seminary, but his first poems were published in 1853. In 1856, Nikitin collected his first book of poems and, with the help of gr. D. I. Tolstoy published it. From that time on, he entered the secular circle of Voronezh society and expanded his acquaintances. In 1854 he began to write the poem "The Fist", which he completed in 1857. In 1858 the poem was published as a separate edition.

In 1859, N., together with Kurbatov, opened a bookstore in Voronezh and a reading room attached to it. N.'s enterprise pursued not only commercial, but also cultural goals. The business of the store went well, but Nikitin's health, which had been undermined earlier due to continuous worries, was getting worse and worse. The poet died at the age of 37.

N.'s creativity developed in the period preceding the reforms of 1861, during the period of Russia's decisive shift towards industrial capitalism. The pre-reform philistinism, whose ideologist was N., was a complex and undifferentiated petty-bourgeois group that retained in its way of life and ideology many of the patriarchal features that had developed during the period of feudalism. Social status this group at the turn of the 1960s. was especially contradictory: on the one hand, developing capitalism ruined the bourgeoisie, on the other hand, individual strata of it had prospects for developing into the merchant bourgeoisie, into the kulaks, even into the industrial bourgeoisie. The petty bourgeoisie singled out from their midst the raznochintsy, who became the ideologists of peasant democracy.

Creativity N. and reveals in figurative form these possible ways of development of his class group. Need, the burden of labor, hopeless grief, eternal longing - this is the first complex of ideas and feelings that found expression in the work of N. It is revealed, for example. in the image of Taras (the poem "Taras"). His life is a hard, but honest path of a worker, who, in the conditions of developing capitalism in the 40-50s. especially acutely feels the possibility, the constant threat of being thrown into the abyss of poverty. Hence his terrible anxiety and attempts to find another, more stable position. Taras goes to barge haulers, abandons his family, breaks with the peasantry, but all to no avail. To accumulate a treasury, to get rid of need, to live in peace, he fails. N. sees no way out for this image, and Taras perishes in the waves, saving a drowning man. Difficulty and hopelessness life path the poor are shown by N. in the image of Lukich in the poem "The Fist". The image of Lukich is poeticized by N., he put his sincere thoughts and feelings into it, fully aware that "And I might have to follow your path ... All the dirt and poverty of the kulak was close to my soul." Depicting Lukich, N. sought to arouse sympathy and pity for him, to show in his fist, first of all, a man forced by poverty to rough exploitation: "You are terrible, the fatal force of Need and petty evil." Staring at such a task, N. shows the cherished dream of the bourgeoisie to get out of the swamp, "to go out into the people." The old woman-wife, daughter Sasha, neighbor-carpenter - everything is sacrificed to one desire - to become a merchant. The fate of Lukich, at the same time, speaks of the futility of the share of the poor - the contentment achieved by rough exploitation is unstable. Lukich understands the possibility of another path, but does not want to follow it: "What is honesty, if there is no altyn. You will bend unwillingly in a ring Before a wealthy rogue." Lukich is indignant at his son-in-law, at the rich in general, but not because he considers them a harmful social phenomenon, but only for selfish reasons - they left him to the mercy of fate, they forgot. The image of Lukich is not alone in N. (compare, for example, his play "Stubborn Father", "Overnight Cabins", etc.). N. emphasizes that Lukich is worthy of all sympathy and respect, because he is first of all a man, and what a fist he is: Not a trifle, not a penny rogue..."

Like all other artists of his era, N. could not pass over in silence the central problem of this time - the attitude towards the peasant; It is on this question that the social nature of the I. and its place in the class struggle are completely exposed. In the pre-reform years, the urban philistine strata had not yet sufficiently differentiated themselves from the countryside, with which they were linked both genetically and by economic conditions. A number of moments of a biographical order (constant connection with the peasant during the period of maintenance of the inn, connection with the village during the period of the book trade) also contributed to the development of village motifs in N.; this feature makes N. related to Koltsov ( cm.) and a number of other petty-bourgeois poets. N. painted realistic pictures of the downtroddenness and oppression of the peasant, his needs and grief, the suffering of the broad peasant masses and the urban philistine strata ("Vengeance", "Overnight cabmen", "Quarrel", "Stubborn father", "Coachman's wife", "Burlak" , "Corruption", "Coachman's Tale", "Peasant's Tale", "Delezh", "Need", "Beggar", "Poor Village", "Grandfather", "Nryakha", "Dead Body", "Old Servant", "On the Ashes", "Tailor", "Master", etc.), exposed dirt, wildness, unbearable difficult conditions the existence of the peasantry in the era of serfdom. But serfdom, the agrarian question, and the struggle of the revolutionaries against the liberals had little effect on N. N.'s attention and sympathy for the muzhik have a peculiar character. N. depicts the peasant as invariably submissive to his fate and patiently enduring its blows. "Old Servant" reveals slavish obedience, the complete absence of protest - traits born of the serfdom. N. is sensitive to those traits social psychology peasantry, which were also characteristic of the environment of the provincial urban tradesman. Stupidity in a dispute over an old collar ("Delezh"), faith in healers and brownies ("Attempt", "Unsuccessful dryness"), oppressive poverty ("The Coachman's Wife", "On the Ashes", "Overnight in the Village", "Beggar" etc.) and the fight against her, pushing her to crime ("Dead Body") - all these features are too general to give the image of the peasant as a special, different from the image of the urban poor, the tradesman.

The social conditionality of N.'s work showed up here in its entirety: he acted not as an ideologue of revolutionary peasant democracy, but simply as a democrat of the reformist, gradualist type. Instead of a revolutionary protest against serfdom, N. remained at the stage of sympathy for the suffering and severity of peasant life. N. saw poverty, overwork, cruel and merciless struggle for a piece of daily bread, he pitied the people, bowed before their patience and suffering: "That's where you need to learn to believe and endure." Instead of a call to struggle, to revolutionary denial, he preached gradualism: "Time moves slowly - Believe, hope and wait ..." The most attractive for N. N. himself dreamed of achieving for himself what Evgraf Antipych achieved - to acquire a farm, a farm, housing, agricultural tools, horses, servants, etc. Evgraf is not a landowner, but a merchant who has acquired a farm. Its purpose is not at all to conduct a subsistence economy, but to conduct a capitalist, commodity economy. The image of Evgraf is not fully disclosed, but the capitalist master is already quite clearly identified in it. At the same time, we have before us a cultured person who is interested not only in Russian, but also in world literature. On this point, Nikitin's position in the light of the reform of the 60s is most clearly revealed: he is a supporter of the capitalist path of development, he is for the bourgeois order.

Wednesday N. put forward and revolutionary ideologists of peasant democracy. This path was not unknown to N.. Wed in the "Diary of a seminarian" the image of Yablochkin - an educator, thirsty for knowledge and serving society, able-bodied, plebeian proud and independent. It is characteristic, however, that we do not find a clear and precise socio-political program in Yablochkin. A comparison of Yablochkin with Belozersky, with Ivan Yermolaich and the entire seminary milieu clearly shows us the image of a commoner. However, Yablochkin dies - N. does not know how to deploy it further. N. did not understand the social role and significance of the revolutionary raznochintsy.

N.'s fluctuations in relation to Nekrasov are known. Turning to the latter, he said: "Your life, like ours, is barren, Hypocritical, empty and gone ... You did not understand the sadness of the people, You did not mourn the bitter evil" ("To the accuser poet"). N.'s poems, permeated with nationalism and chauvinism, speak of an even greater misunderstanding of modern political reality: "Rus", "Donets", "War for the Faith", "South and North", "New Struggle", etc. N. sings of strength and power Nikolaev monarchy on the eve of its defeat. It was these chauvinistic works that forced the reactionary c. D. I. Tolstoy to take part in the first edition of N.'s poems. On his own advice, the author presented his collection to the highest persons and was awarded a gift.

Another stroke finishes us the reactionary side of the literary portrait of N. - religiosity. Poems of religious and philosophical content show that N. could not cope with these issues; could not rise to the level of the advanced ideas of his time. "Prayer", "Prayer of a Child", "Prayer for a Chalice", "Life and Death", "Calmness", "Sweetness of Prayer", etc. show that I. wanted to believe in a higher power that resolves all doubts.

Misunderstanding of revolutionary democracy, patriotism and loyalty, along with the dream of the material contentment of the poor in the conditions of the existing political system characterize N. as a gradualist liberal. But the democratic protest against the poverty and oppression of the peasant and philistine masses, the ardent love for these masses had a historically positive significance in the pre-reform period.

Revolutionary-democratic criticism greeted N. unfriendly, outraged in particular by his patriotic poems and admiration for tsarism. There is a well-known sharp review of Chernyshevsky, who denied N. talent. But later revolutionary-democratic criticism also noted the positive aspects of N.'s work. Dobrolyubov captured the social meaning of his work most correctly. N. Chernyshevsky attacked N. as an artist, seeing in him, of course, a person of a different camp. Chernyshevsky pointed out that N. was not independent, not original, that he borrowed from Koltsov. Pushkin, Lermontov, Maykov, Shcherbina, etc. In fact, N. does not imitate everywhere, he has independence, originality, and originality. Where he interprets questions close, dear - questions of everyday life, landscape, the life of a peasant and a tradesman - he finds his words and his images.

Nikitin sometimes used those developments of verse that Koltsov gave, going in this respect much further than his predecessor (for example, the poems "Rus", "Old Miller", "Departure of the Coachman", etc.). N. is connected with Koltsov not only through the development of poetry, but also ideologically: they are representatives of the same social environment, ideologists of the same social group, which was at different stages of development and in several different positions. Nikitin goes further than Koltsov, developing new themes and images.

Not being an innovator in the field of verse, N. however, revealed the contradictory ideology of his class with sufficient clarity. Not free from imitations (for example, Pushkin, Koltsov, Nekrasov), N.'s work nevertheless represents a certain artistic value; Let us point out, for example, his numerous landscape sketches, which over the years have become "classic" and have become part of textbook use (poems "Morning", "Morning on the Lake", "Storm", etc.).

Bibliography: I. Works. With a biography compiled by M. de Poulet. The first posthumous edition, 2 vols., Voronezh, 1869 [the publications, starting from the 4th (M., 1886), ed. the same de Poulet]; ed. 13th, M., 1910; Complete Works and Letters. Checked on manuscripts and early printed sources text and variants, ed., with biographer. essay, articles and notes. A. G. Fomina. Enter. article by Yu. I. Aikhenvald, 3 vols., ed. "Enlightenment", St. Petersburg, 1913-1915 [vol. I. Poems, 1849-1854; vol. II. Poems, 1856-1861, and poems; vol. Sh. Prose; ed. not finished. Volume IV was to include the poet's correspondence and a number of explanatory articles]; The same, 3 vols., ed. Literary-ed. otd. Com. nar. proev., P., 1918 (reprint from the stereotype of the previous edition); Complete Works in 1 volume, ed. M. O. Gershenzon. Moscow, 1912. Same, ed. 3rd, M., 1913; Complete Works, ed. S. M. Gorodetsky. The text is processed according to manuscripts, first editions and journals, 2 vols., ed. "Activist", St. Petersburg, 1912-1913; Works, ed., notes. And he will explain. articles by A. M. Putintsev, no. I. Lyrics, Voronezh, 1922.

II. Except enter. articles of the editors of the above ed. - de Poulet, S. Gorodetsky, A. Fomin and others - see also: Druzhinin A. V., Works, vol. VII, St. Petersburg, 1865; Sivitsky F. E., I. S. Nikitin, his life and literary activity, St. Petersburg, 1893; Mikhailovsky N. K., Works, vol. IV, St. Petersburg, 1897; 4th ed., St. Petersburg, 1909; Ivanov I. I., New cultural force, St. Petersburg, 1901; Grot Ya. K., Proceedings, vol. III, St. Petersburg, 1901; Chernyshevsky N. G., Works, vol. II, St. Petersburg, 1906; Pokrovsky V.I., Ivan Savvich Nikitin, his life and works, M., 1911; History of Russian literature of the 19th century, ed. D. N. Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky, vol. III, M., 1911 (article by V. Cheshikhin); Dobrolyubov N. A., Works, ed. M. K. Lemke, vols. II and IV, St. Petersburg, 1912; Putintsev A. M., Sketches about the life and work of N., Voronezh, 1912; Fomin A. G., Nikitin I. S., "Russian Biographical Dictionary", St. Petersburg, 1914; Putintsev A. M., I. S. Nikitin (Life and work), Voronezh, 1922; Dobrynin M., Nikitin's Image of a Fist, "Literature and Marxism", 1928, IV; Him, Landscape in the work of I. S. Nikitin, "Literature and Marxism", 1929, III; Fatov N. N., Ivan Savvich Nikitin (Life and work), M. - Alma-Ata, 1929; A. V. Koltsov and I. S. Nikitin, Collection, ed. "Nikitinsky subbotniks", Moscow, 1929.

III. Putintsev A. M., Materials for a bibliography about I. S. Nikitin and his writings, "Scientific notes of the Yuriev University", 1906, book. II, and separately, Yuriev, 1906; Vladislavlev I.V., Russian writers, ed. 4th, M. - L., 1924; His, Literature of the Great Decade (1917-1927), vol. I, M. - L., 1928; Mandelstam R. S., Fiction in the assessment of Russian Marxist criticism, ed. N. K. Piksanov, ed. 4th, M. - L., 1928; Piksanov N.K., Regional cultural nests, Moscow - Leningrad, 1928, pp. 108-116 (development of topics for literary works according to the Voronezh cultural nest and N.).

M. Dobrynin.

(Lit. Enz.)

Big biographical encyclopedia. 2009 .

- - , Russian poet. Born into a family of a merchant. He studied at the theological seminary (until 1843). The ruin of his father forced N. to become the owner of the inn. In 1859, N. opened a bookstore, which became important ... ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Ivan Savvich Nikitin is a talented poet and prose writer who worked in the direction of landscape lyrics. Author of the most popular works. His observations of nature and the soul of a commoner are amazing. Nikitin Ivan Savvich, whose portrait photos are presented in the article, even with his whole appearance shows greatness of spirit and great wisdom in life.

Period in history

The main themes in Russian literature of the 19th century were the struggle against autocracy and serfdom. The time when Nikitin was born and died is the period of the struggle against feudalism, the raising of the spirit of patriotism and the birth of the Decembrist movement.

Ivan Savvich also fell under the influence of contemporary literature. He, a poet of the Nekrasov direction, most often painted in his work the socially low strata of society. His poems are characterized by a plot in which peasants and the urban poor are vividly depicted. Often in the works of the author you can find an echo of his own life. Personal poverty also inspires the poet to work.

The poet wrote, taking the works of Nekrasov and Koltsov as an example, but this did not prevent him from developing his own style.

It was the experiences, characteristic of many people of that time, that left a seal on the poems of Ivan Savvich Nikitin. The short works of the author are the pain and joy of that period in the history of Russia.

The childhood of the poet

The life of Ivan Savvich Nikitin was not easy from the very beginning. But, perhaps, everything had turned out differently, fate would not have endowed him with talent.

Nikitin, the future poet, was born on October 3, 1824 in Voronezh, into a simple bourgeois family. His father was a candle merchant and at that time made good money. From an early age, he was taught to read and write by a shoemaker neighbor. Nature gave the boy the greatest joy. For hours he could walk around the neighborhood, observe the changes in the earth. The closeness and detachment of the child did not frighten the parents.

“I am glad of the autumn bad weather: the noise of the crowd is unbearable for me,” Nikitin Ivan Savvich later wrote.

The father had big plans for his son, so he sent him to study at the seminary. It was there that the boy first tried to write poetry.

Prematurity

While the boy was studying, problems began at home. The family business did not work out, and the father began to drink. Moreover, having a very cool character, he was addicted to a glass and the poet's mother. Due to family troubles, the guy was not up to school, and soon he was expelled from the school. From the school desk, he stood up to the counter of the candle shop.

Some time later, Ivan Savvich's mother died. After a while, the business completely outlived itself. And the only thing that made the guy happy was literature. However, one could forget about dreams of studying at the university.

Striving for beauty

So sadly passed the years of the life of Nikitin Ivan Savvich. Hard work, a despot-drunk father and gray, similar days. But the spark that drew the poet to the beautiful, everyday life could not extinguish. He strives for high art and never ceases to absorb the work of Pushkin, Gogol, Shakespeare and his favorite Belinsky. What remains of the candle shop, the young man exchanges for an inn. And among the always drunk and noisy clients, the future poet managed to allocate time for writing poetry.

The unsociable lonely Nikitin found more happiness in these short moments than in the senseless waste of time talking to people. Gradually, a poet began to grow in him. Poems by Ivan Savvich Nikitin are short, but correctly composed and meaningful.

First step to success

In November 1853, the young man decided to send his works to the editor. They are published in the publication "Voronezh Gubernskie Vedomosti". Then the author signed with the initials “I. N.". Nikolai Vtorov worked at the newspaper publication, who not only became interested in the young poet, but later became his best friend.

The works quickly received positive reviews and brought fame to the young poet. Nikitin Ivan Savvich became Koltsov's "successor". He beautifully extols nature, love for the earth sounds in his works, he sings of the beauty of a simple working person. In addition, he has since been accepted into the circle of intellectuals. Finally, he revolves around people with whom he is interested.

One of the three poems he sent to the editor was "Rus". In this work, he expressed his pain and patriotic sentiments associated with the Crimean War.

Source of inspiration

Despite the glory, the life of the hero of our story has changed little. The poet Nikitin Ivan Savvich did not stop working at the inn. My father still drank, but in 1854-1856 the relationship between them improved a little. The atmosphere that prevailed in the courtyard often inspired the writer. There one could eavesdrop on the conversations of ordinary people, enrich the imagination with new images, observe sulfur, but interesting life. And this was so necessary for Nikitin for creativity.

Also during these years, the poet was engaged in self-education, got acquainted with the works of other writers, studied French.

What is the spiritual power of the poet

In the summer of 1855, the poet caught a cold from swimming and blew up his already poor health. During that period, he turns to faith and pours out his feelings in poetry. In sad moments, such poems as “Prayer” (1851), “New Testament” (1853), “Sweetness of Prayer” (1854) came out from under his pen. These are the most religious years of the life of Nikitin Ivan Savvich. Short works touch to the depths of the soul with their simplicity and depth of content:

"Oh my God! give me will power

Mind doubt dead.

In 1857, one of the few comrades of the poet, Nikolai Vtorov, left Voronezh. Melancholy attacks the master of the pen, for a while his creative forces leave him. But the same mood did not rule over the poet for long, and he splashes out his experiences, negative emotions and loss of strength on paper. So, next year, the work “Fist” comes out from under his pen. The poem was received very well by critics and readers.

Autobiographical "Fist"

In the years when Nikitin was born and died, in Russia there was such a thing as a “fist”.

It meant a merchant who profits from the fact that he measures, weighs and deceives people. The protagonist of the work is the merchant Lukic. He leads a wrong and dishonest way of life, not embarrassed to steal, lie and cheat. These little crafty deeds are the only thing on which he and his family live. The poem is partly biographical. The merchant and his wife are the author's parents. The everyday scenes he described are moments that he saw with his own eyes.

The poem "The Fist" turned out to be very rich in life episodes. Her speech is fresh, and the description of nature is fascinating. There are parts that could become independent verses if taken out of context. The poem deserves the title of national treasure. In no other work is life described so vividly.

The poet's childhood was difficult, and "The Fist" is to some extent his biography. Ivan Savvich Nikitin lived at a time when drunkenness was very common. The poem fully reflected the then state of the Russian Empire. Therefore, having described the problems of his family, he characterized the entire society of that time.

The sunset of a short life

A year later, in 1858, the second collection of poems was published. Critics did not appreciate the work, but this did not prevent the poet from doing what he loved. He continues to study and is now engaged in translations, which helps him to better understand the rich world of literature.

In February 1859, Nikitin opened a bookstore, to which a library was attached. In Voronezh, the shop becomes a center of culture for the common people and the intelligentsia.

At the time when Nikitin was born and died, it was precisely such bookstores that collected the bright minds of society.

Since that time, the poet's health began to deteriorate. When he felt well, his work was replenished with new works. But during his illness, the poet could not be interested in almost anything that surrounded him.

The diary of a seminarian was written by the poet a year before his death. It was his first prose work.

Fees for creativity allowed him to become financially independent.

With good health, he travels, visits St. Petersburg and Moscow, actively participates in the cultural growth of his native Voronezh.

May 1861 became fatal for the hero of our story. The poet caught a cold, fought the disease for a long and hard time.

Not simple, thorny was his biography. Ivan Savvich Nikitin died of consumption on October 16, 1861 at the age of 37.

The time of his career was only 8 years.

The poet was buried at the Novo-Mitrofanevsky cemetery, close to another chanter of nature - Koltsov.

The poet was alone when he was born, and Nikitin also died alone. Due to his closed nature, it was difficult for a man to get along with people. The mother passed away young. And the father, even when his son was on his deathbed, did not refuse the bottle.

Even during his lifetime, Nikitin gained fame. Almost two hundred years have passed since the birth of the poet, and his poems, glorifying nature, patriotism and accurately conveying folk images, still remain interesting and relevant.

Ivan Nikitich Nikitin

(circa 1690 (?) - 1742) - the son of the priest Nikita Nikitin, who served in Izmailovo, the brother of the priest Herodion Nikitin, later archpriest of the Archangel Cathedral in the Kremlin, and the painter Roman Nikitin.

Nothing is known about the artist's early years of study. He probably received his initial artistic skills under the guidance of the Dutchman A. Shkhonebek in the engraving workshop at the Moscow Armory. In 1711, together with the engraving workshop, Nikitin was transferred to St. Petersburg. Apparently, he learned to paint portraits on his own, studying and copying the works of foreign masters available in Russia. Thanks to relatives who served in the court churches, Nikitin quickly took a strong position in the environment of Peter I.

"Personal affairs master", favorite artist of Peter I,

I. N. Nikitin was an example of the patriotic pride of the Russian tsar in front of foreigners, "so that they know that there are good craftsmen among our people." And Peter was not mistaken: "the painter Ivan" was the first Russian portrait painter of the European level.

His work is the beginning of Russian painting of the new time.

The year of Nikitin's birth is not exactly known, and the traditionally accepted date of around 1690 is sometimes disputed. Only recently did the patronymic of the artist come to light; as a result of archival research, his figure was separated from another Nikitin, his namesake; only in last years the circle of his works was determined, cleared of copies attributed to him and paintings by other artists. So what is known about the fate of the master of great talent and tragic life?

Ivan Nikitich Nikitin was born into a priestly family, very close to the court. In Izmailovo, the family estate of the Romanovs, the artist spent his childhood. He studied, most likely, at the Armory - only there it was possible to master the craft of a painter. However, even in the earliest Nikitin works, an acquaintance with European painting is found.

Nikitin left Moscow in 1711, when all the masters of the Armory were transferred to the new capital. Here, at the newly founded St. Petersburg Printing House, a drawing school was soon founded, in which "masters and painters of grydorovy affairs ... received the best science in drawing." Among the teachers - Ivan Nikitin.

In the early (before 1716) works of the artist, there is a clear connection with the parsuns of the late 17th century. They are distinguished by hard writing, deaf dark backgrounds, flatness of the image, lack of deep space and conventionality of black and white modeling. Early works include the following portraits of him

Nikitin Ivan Nikitich. Portrait of Elizabeth Petrovna as a child. 1712-13

The portrait of the daughter of Peter I, Elizabeth (1709-1761), the future empress (since 1741) is the earliest of the known 18 paintings by the court artist of Peter I. There is some stiffness in the depiction of the figure, flatness in the interpretation of the costume and background, but the lively image of the girl is full charm. One can feel the desire of the artist to convey not only the external resemblance, but also the mood, to reveal the inner world of the person being portrayed. A child's magnificent full dress, a heavy dress with a large neckline, an ermine mantle on the shoulders, an adult lady's high hairstyle are a tribute to the requirements of the times.

I.N. Nikitin. Portrait of Princess Praskovya Ivanovna. 1714. Timing

Praskovya Ivanovna (1694-1731) - princess, youngest daughter of Tsar Ivan V Alekseevich and Tsarina Praskovya Feodorovna (nee Saltykova), niece of Peter I. Lived with her mother in Izmailovo near Moscow.

Peter gave his nieces in marriage to foreign dukes, while pursuing political goals. But this was not always possible: “... the youngest, Praskovya Ioannovna, “lame”, sickly and weak, “quiet and modest”, as contemporaries noted, for a long time resisted the iron will of the tsar and, as a result, secretly married her beloved, Senator I. I. Dmitriev-Mamonov.

In the portrait of Ivan Nikitin, Praskovya Ioannovna is 19 years old, her marriage is still ahead. She is dressed in a blue and gold brocade dress, on her shoulders is a red mantle with an ermine. The background of the portrait is neutral, dark. How was this portrait painted by the artist?... In Nikitin's portrait, many of the generally accepted (in the European sense, in the understanding of new art) semantic and compositional features of the easel painting are violated. This primarily affects the departure from anatomical correctness, direct perspective, the illusion of the depth of space, and light and shade modeling of the form. Only a subtle sense of texture is obvious - the softness of velvet, the heaviness of brocade, the sophistication of silky ermine - which, let's not forget, is well known to painters of the last century. In the pictorial manner, one can feel the old techniques of highlighting (“flying by sankir”) from dark to light, the pose is static, the volume does not have energetic pictorial modeling, the rich color is built on a combination of major local spots: red, black, white, brown, exquisitely shimmering gold of the brocade The face and neck are painted in two tones: warm, the same everywhere in the illuminated areas, and cold olive in the shadows.

There are no color reflections. The light is even and diffused. The background is flat almost everywhere, only around the head it is somewhat deepened, as if the artist is trying to build a spatial environment. The face, hairstyle, chest, shoulders are painted rather according to the principle of the 17th century. - as an artist "knows", and not as "sees", trying to carefully copy, and not reproduce the design of the form. And the folds are brittle, written with white strokes, a bit reminiscent of old Russian spaces. Against this background, as already mentioned, the brocade is quite unexpectedly boldly written, with a sense of its “thingness”. Moreover, all these luxurious grand ducal clothes are only discreetly marked with details, to the extent that the master needs to represent the model. But the main difference of the portrait seems not in this mixture of techniques and in the originality of the molding of the form, the main thing is that here we can already talk about the individual, about individuality - of course, to the extent that it is present in the model. , self-esteem. The center of the composition is a face with large eyes looking sadly at the viewer. A folk saying about such eyes says that they are the "mirror of the soul." The lips are tightly compressed, there is no shadow of coquetry, there is nothing ostentatious in this face, but there is an immersion in oneself, which is outwardly expressed in a feeling of peace, silence, static. “The beautiful should be majestic” (Ilyina T.V. Russian art of the XVIII century. - M .: Higher School, 1999. P. 65-66.).

I.N. Nikitin, Portrait of Princess Natalya Alekseevna, no later than 1716, State Tretyakov Gallery

Natalya Alekseevna (1673-1716) - daughter of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and his second wife, Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina, beloved sister of Peter I.

Natalya Alekseevna was a supporter of Peter the Great's reforms, and was reputed to be one of the most educated Russian women of her time. The development of the Russian theater is associated with her name. She composed plays, mainly based on hagiographic subjects, and staged theatrical performances at her court. Count Bassevich, minister of the Duke of Holstein at the St. Petersburg court, wrote in his Notes: “Princess Natalia, the younger sister of the Emperor, very beloved by him, composed, they say, at the end of her life two or three plays, quite well thought out and not devoid of some beauties in details; but due to the lack of actors, they were not put on stage ”(Notes of the Holstein Minister Count Bassevich, which serve to explain some events from the reign of Peter the Great (1713-1725) // Russian Archive. 1885. Issue 64. Part 5-6. C .601).

It is no coincidence that in the portrait she is already dressed according to a new model: the style of the dress, the wig, the pose - the whole appearance speaks of her belonging to the new time, to the era of the transformation of Russia.

However, among visual means the painter, there are those that still belong to the icon painting: a monochromatic background, a certain flatness of the figure; the curves and folds of the dress are conventional and too rigid. However, the face of the princess is written quite voluminously.

The artist portrayed Natalya Alekseevna shortly before her death. She was ill for a long time and died in the same year 1716 - she was a little over forty years old. Perhaps because of this, some sadness is read in her portrait. The face is written out slightly swollen, with a painful yellowness, which does credit to the keen eye of the artist.

It must be assumed that the portrait belonged to Natalya Alekseevna herself. According to S. O. Androsov, a more accurate dating of the work is around 1714-1715 (Androsov S. O. Painter Ivan Nikitin. - St. Petersburg, 1998. P. 30).

Another work of the first period of Nikitin's work is a portrait of Tsesarevna Anna Petrovna (until 1716), Peter's daughter.

I.N. Nikitin, Portrait of Princess Anna Petrovna, no later than 1716, State Tretyakov Gallery

The portrait shows traces of parsun writing. Nikitin still violates many European rules for depicting a person. This primarily affects the deviations from anatomical accuracy, direct perspective, there is no full-fledged illusion of the depth of space, black-and-white modeling of the form.

Anna Petrovna (1708-1728) - eldest daughter Peter I and Catherine I. In 1725 she married Duke Karl Friedrich Holstein-Gotorsky. Mother of Emperor Peter III.

Portrait of Empress Praskovya Feodorovna Saltykova

This canvas was in the gallery of the Archimandrite's house. In the semi-ceremonial portrait, solved in a calm brown tones, a closed and proud nature appears. Praskovya Fyodorovna Saltykova (1664-1723) became empress in 1684, having married the elder brother of Peter I, Ivan Alekseevich. Twelve years later, Praskovya became a widow, but in the documents of the 18th century she is respectfully referred to as "Her Majesty Empress Empress Praskoveya Feodorovna." Empress Praskovya had three daughters - Ekaterina, Anna and Praskovya.

Apparently, Peter highly appreciated these works: soon Nikitin began the first royal order, which we know about only from the entry of Peter's Journal: "His Majesty's half person was painted by Ivan Nikitin."

At the beginning of 1716, Nikitin went to study abroad, to Italy, where his stay greatly expanded the techniques of his painting.

Nikitin Ivan Nikitich. Portrait of Empress Catherine I. 1717, Florence, Ministry of Finance, Italy

Nikitin Ivan Nikitich. Portrait of Peter I. 1717

At the beginning of April 1720, the Nikitin brothers returned to St. Petersburg, met with royal affection - Ivan received the title of Hoffmaler. His life was now closely connected with the court.

Ivan Nikitich Nikitin - Portrait of Peter I, Russian Museum, First half of the 1720s